Athletes Authority

Latest Blog & Insights

Are You A Marxist Strength Coach?

The works of Ciaran O’Regan, Mladen Jovanovic, Mike Tuscherer and John Kiely were profound influences on this article. For a more extensive understanding of Top-Down Training Planning, I’d highly recommend looking into their work.

How the strength coach community has been manipulated by Marxist ideology… and why you’re probably none the wiser.

Here is an inconvenient truth — almost everything you know about the planning of athletic training for sports — what us strength coaches call ‘periodisation’, is adapted by the work of an academically inclined factory supervisor called Frederick Taylor. In his 1911 book Principles of Scientific Management, he put forth the idea that there was a ‘best-practice’ of planning within the manufacturing industry that would improve efficiency and optimise output. Coined Taylorism, this form of organisational management reduced the problems of planning and production to a set of formulas, rules and automated solutions, providing immediate appeal for a world who was in desperate need of scale and simplicity. Originally applied to manufacturing with great success, it was quickly adapted to other industries including Governmental planning, which is where this historical account gets interesting.

Principles Of Scientific Management, published 1909.

When a young Marxist and political revolutionist Vladimir Lennin got hold of Taylor’s ‘best-practice’, plan-in-advance approach to management, he applied these ideas to the newly formed USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics). Now a Communist State, Taylor’s approach to organisational management sat nicely as a model for management underneath the umbrella of Marxist ideology.

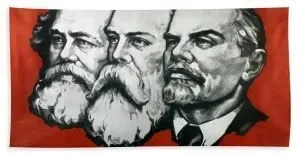

From Left: Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels & Vladimir Lennin

For those not politically inclined, Marxist ideology advocates for collective or governmental ownership and administration of the means of production and distribution of goods. In layman terms: the state owns everything, and the state distributes everything from the top, down to the bottom. Top Down Planning (TDP), especially applied to the human domain — is the utopian pipedream based on the misdirected notion that one (or few) people, can account for every relevant factor and, effectively centrally plan for the needs of a society (or an organisation) from the top down.

This form of centralised, long-term planning was popularised by Stalin’s 5-Year Economic Plan within the USSR, which concentrated on developing heavy industry and collectivizing agriculture, at the cost of a drastic fall in consumer goods. Long-term planning continued, with a second plan (1933–37) following on from the same objectives as the first.

Over the following decades, long-term planning within the Soviet Union became pervasive that it finally found its way to the state-governed sports programs of the USSR. Deeply seeded in these sports program was the notion that there was a best-practice approach to the planning of sports, and that it involved detailed planning in advance — Macro > Meso > Micro cycles in accordance with the Olympic cycle. From this idea came the birth of modern periodisation that we know today.

Example of a traditional periodisation model

Even though only a few have made the connection — Kiely, Turscherer, Jovanovic and O’Regan (I’m sure there are others I have missed), modern periodisation is nothing more than an adoption of these principles — stipulating that there is a best-practice in the planning of training for sports and that it should occur from the top, down.

Take a second and jog the memory bank for all the iconic periodisation textbooks. Note the authors.

Tudor Bompa… born in the USSR. Matveyev… also born in the USSR. Vladimir Issurin, again, Soviet born. Prilepen… Soviet.

In case you hadn’t realised, almost all the original pioneers of long-term training planning and the forefathers of modern periodisation that the strength coach community seem to hold on a pedestal, were Soviets who knew only long-term, best-practice, sports planning.

This isn’t coincidence. This is a result of the systemic, state-wide implementation of Marxist ideology and long-term planning across all aspects of Soviet society — government, agriculture, manufacturing and even sports. It would seem that long-term planning would go hand-in-hand, with the hammer and sickle.

Of course, it’s important to note that Marxist ideology, in practice, has always failed. Stalin tried it, and failed his people. Castro tried it, and failed his people. Maduro inherited it, and failed his people. Mao tried it, and to no one’s surprise, failed his people.

So this raises an important question: if TDP ultimately fails as a framework for the management of human society, why has it persisted so strongly within the strength and conditioning context?

For that, we’ll need to go back to understanding a little more about Taylor’s ideas.

Something central to the success of Taylor’s ideas was the reliance on ‘the best men’ to facilitate ‘best-practice’. It hypothesised that rather than simply assigning workers to just any job, you should match workers to their jobs based on capability and motivation, and train them to work at maximum efficiency. For TDP to work, as many variables as possible needed to be accounted for; and one of those happened to be talent.

Taylorism would ultimately fail in Soviet Russia. The widespread Communist workforce were unable to rely on the best talent — the demands for production were simply too high to source only the ‘best men.’ But unlike its failings within the workforce, the USSR sports programs had access to the best talent in enormous supply — they had as Taylor would put it ‘the best men.’

Perhaps one of the greatest achievements you could ever make for Mother Russia was to represent your Country and your Comrades on the global sporting stage. Sporting success became a more peaceful representation of Mother Russia’s might and power — it was a global force to be reckoned with.

In fact, from 1952 (the first Olympic Games as the USSR following the extended break during WWII) all the way through to the demise in 1991, Russia was either first, or second in the total medal tally.

Source, Wikipedia.

The National pride associated with a world class sports performance meant that there were talented men and women in almost infinite supply to put through a TDP approach (what I will now refer to as Top Down Training Planning (TDTP)). With an endless supply of talent, sports scientists (like the aforementioned authors of our periodisation textbooks) could apply a TDTP approach and if the athlete couldn’t cope, it’s hypothesised that they would simply fade away back to the government-elected job that they came from.

This cannot be understated enough. With an endless supply of talent, TDTP works. If an athlete can survive rigid TDTP that reverse engineers a gold medal performance, then it’s a winning formula. However, outside of state-funded sports programs with huge national populations to draw talent from (aka in the real world where 99.9% of strength coaches live and operate), TDTP falls apart like a house built by a deck of cards.

In the real world, strength coaches don’t have unlimited talent at their disposal, nor, can they mitigate the effect of unknowns on the outcome. Rather, the everyday sports scientist/strength coach is looking after the local rugby team who is arguably, as talented at drinking beer as they are at playing rugby; or, they’re training an athlete that is juggling studies, a part-time job and a rocky relationship all the while saying they will sacrifice anything for their dream; or, they have a talented footballer with one caveat — they’ve never stepped foot in a gym in their life and have heard it ‘makes them slow.’

Despite these realities, TDTP is alive and well. You don’t have to look far to find a strength coach — many of whom have achieved notoriety — sell a 12 week (set-and-forget) training program delivered in advance promising superior results (full disclosure: in my naivety, I have commissioned exactly the same thing). You don’t have to look far to see athletes struggle to complete training because their coach wrote their program weeks ago, failing to realise the athlete was maladapting to the stimulus. And every day, there is a strength coach madly panicking about their long-term training plan turning to shit because so-and-so superstar player got injured and the head coach wants <insert dinosaur punishment here> after a poor performance; resulting in a cataclysmic shit-storm that any strength coach worth his salt has been caught in the centre of, at least once in their career.

As idealistic as long-term training plans are, it is not the real world. Instead, it is in complex environments that the vast majority of strength coaches refine their craft. Only the smallest minority — like the Soviet forefathers who wrote our textbooks — call their place of work a state-owned sports performance centre funded and maintained by Mother Russia.

In recent years, this Achilles heel of TDTP has been critiqued by Mike Turscherer, John Kiely, and more recently, by Mladen Jovanic in his book ‘Strength Training Manual.’

This critique has been for good reason: TDTP, like Marxism, emphasises that there is a ‘best-practice’ when implementing an intervention; that there is the ‘right’ way, and that every other way is inferior. Whether you’re in the block periodisation camp, the linear periodisation camp, the undulating periodisation camp, the vertical periodisation camp or what-ever-phase-is-sexy-today periodisation camp, you’ll find strength coaches passionately defending their version of ‘best-practice’, and, every aspiring strength coach forking out $$$ to learn the secrets of mastering top down training planning as if it will magically create unicorn athletes and catapult their career success.

This of course, is a form of cognitive arrogance because the old adage of “the more we know, the more we realise we don’t know” holds true for strength training planning and prescription. This cognitive arrogance is often called epistemic arrogance, and it represents the feeble attempt by naive (or perhaps just traditionalist) strength coaches to rigidly account for the outcomes of the athlete well in advance of them actually happening.

Strength coaches who subscribe blindly to these ideas, not considering the practical, day-to-day implications and variance of real-world sports training are the coaching equivalent of political socialists that advocate for a utopian existence where everything falls into place just perfectly. In this utopia, every inequality can be accounted for, all marginalisation can be eradicated, diversity and individual differences can be embraced in perfect harmony, inclusivity can be welcomed and human suffering can be abolished.

As history has taught us, and reality continues to demonstrate, TDP doesn’t account for the fact that human society is a complex system and the interactions between its constituent parts do not have cause-effect relationships. Simply, the outcomes that emerge from complex systems can only be observed after the fact, rather than predicted in advance. This concept is explored with the Cynefin Framework, shown in the picture below.

Cynefin Framework as of 2014 (Snowden)

Perhaps the greatest dilemma with TDP (and by extension, TDTP) stems from it’s misplaced categorisation of the human system — the very nature of ‘best practice’ relies on obvious cause and effect relationships. It’s obvious that being hit by a speeding truck will leave you second best, and therefore, best practice is to not walk in front of speeding trucks. It’s certainly not obvious however, how an athlete will respond to a twelve week block of training planned in advance and by the same token, there is no such thing as best-practice.

In fact, humans don’t even fit in the domain of ‘complicated.’ Human beings are not like cars or computers and we cannot simply work rationally toward a decision and outcome via expertise alone — we can’t pull a human apart and put it back together and expect it to operate the same. The very nature of pulling apart a human being in the first instance changes the situation in ways you cannot possibly comprehend completely.

For that reason, the human being is a complex system. This, according to Dave Snowden (the man responsible for the model), describes this domain as the “unknown unknowns” (we don’t know what we don’t know). “Cause and effect can only be deduced in retrospect, and therefore, there are no right answers. Instructive patterns emerge over time, writes Snowden, “[and is dependant on]…the leader conduct[ing] experiments that are safe to fail.”

Cynefin (pronounced Kee-Nee-Ven) calls this process “probe–sense–respond”. Humans, battlefields, markets, ecosystems and corporate cultures are examples of complex systems that are “impervious to a reductionist, take-it-apart-and-see-how-it-works approach, because your very actions change the situation in unpredictable ways” writes Snowden.

Here is an example of how you might interpret the Cynefin model to the planning of training for athletes:

Probe = Write a program that is minimally viable, that is safe-to-fail (if it fails, it doesn’t cause irreparable damage) and ticks off the significant training qualities you want to improve.

Sense = Determine how the athlete(s) responds to the stimulus (did it fail or succeed?).

Respond = Iterate, experiment and adapt the program accordingly.

In the same way human societies are complex systems, so is the human individual. Humans are fractals in this sense: it doesn’t matter if we look at human beings at the cellular level, or, the societal level, they remain complex at every level of resolution (that isn’t to say that humans respond predictably at scale — individual anarchists are usually pretty harmless, until they are handed a Molotov cocktail amongst a mob of other anarchists just like them).

This is why Marxist ideology is so arrogant in relation to knowledge — it thinks the knowledge of a few (or in the context of training prescription, one coach with one perspective) has sufficient knowledge to optimally and centrally plan for the needs of a complex system made up of other equally and uniquely complex systems. The sheer scale of knowledge that isn’t known is simply too great to make an accurate prediction on how to plan effectively for what is to come. Any strength coach who has ever been responsible for a team (or even an individual over an extended period of time) knows that at some point in time, everything turns to shit and no amount of long term planning will save you. As the great Mike Tyson put it:

“Everyone has a plan until they’re punched in the face.”

Bringing this back to strength training, if you take a sample of strength athletes, each individual athlete is a complex system. If this athlete happens to be part of a team, then the athlete is one complex system existing within a larger, complex system. The training stimulus imposed on the athlete happens to be just one variable in a host of other variables that influence how the athlete reacts and adapts.

If you want to think of it another way, the complexity of the human system does not adapt to a specific, isolated training stress but rather, how that specific stress fits into the bigger picture of their physiology given their current conditions.

O’Regan suggests that you can think of adaptation in three ways: Null adaptation (/A), negative adaptation (-A), and positive adaptation (+A).

/A = the training is neither effective at producing the desired adaptation, or consequential that it produces an undesired adaptation.

-A = the training is too stressful and the person adapts maladapts.

+A = the training is optimally stressful and was neither too easy for /A, or too much for NA.

For a certain athlete at different points in time, a training stimulus could be all three of these.

Take the following example:

Athlete X is getting good sleep. The head coach has good things to say about his game performances; he is getting good sleep; he’s having sex and, he is getting his bonus cheque because the team is winning. The training he does in the gym might be resulting in a positive adaptation and Athlete X is getting better. Or, if he has unfortunately been assigned a Marxist Coach that plans in advance and doesn’t adjust as outcomes emerge to accommodate for individual differences, he may be getting an insufficient training stimulus and undercooking himself.

In another example, the same athlete may be getting poor sleep because of night-time roadworks, his coach is on him for bad technique, his girlfriend is turning her back when he makes the evening move, and he got relegated to reserve grade for inconsistency on game day. That very same training stimulus now may be, maladaptive.

Here is just a small list of some of the factors that come into play here that ultimately, affect the internal physiology of the athlete and the outcomes that emerge:

Injury history and current injury presentation

Allostatic accomodations

Fitness level

Athlete mindset

Nutritional considerations

Individual genetics

Sleep quality

Competition stress

Relationships

Career

Training age

Maturation

Head Coach expectations

As you can see, just this small list makes it almost impossible to pre-plan well in advance for training. TDTP serves only minimal utility and that is, to provide a loose framework for the direction of training planning — certainly not to the extensive degree in which periodisation textbooks suggest.

So what can we do about this? How do we marry the needs of needing direction for training (TDTP), and needing to be flexible enough to adapt for emergent outcomes?

You’ll Find out in Part 2. Stay Tuned.

Get back to doing what you love, faster. Our Sports Physiotherapy Program works even if you haven't gotten much benefit from tradition physiotherapy in the past. Click here to learn more.

Our resources

Master your mental game Mini Course

Discover the mindset strategies of the World’s Greatest Athletes so you can turn your mind into a weapon of performance.

THE ATHLETES AUTHORITY RECOVERY SYSTEM

Performance = fitness – fatigue. Reduce your fatigue and recover faster with our 3-step recovery system.

MELBOURNE LOCATION

SYDNEY LOCATION

© 2023, Athletes Authority | All Rights Reserved

Website & Marketing Powered By Gymini